Experimental Study: TikTok & Short-term Memory

My Role: Research on a team of 4 for a graduate-level class

Methods: Literature review, Experimental study design, Data Analysis (Inferential statistics), Presentation of findings

Tools: Qualtrics, Google Sheets, Zoom

Timeline: Oct-Dec 2022

Overview:

With the increase of TikTok in our lives, our team was curious about the cognitive effects of TikTok usage, and in particular, how it correlates to working memory.

My Role:

I collaborated with my team to:

conduct a literature review

design a study

write two moderator’s scripts

recruit participants

moderate participants

analyze the data

create final report and present to our professor and the class

Literature Review:

We consulted existing literature to learn current understandings of short-term (working) memory in correlation with phone usage, particularly with social media. A 2021 study highlighted findings that use of TikTok is likely consistent with symptoms associated with other social media platforms such as anxiety, depression, memory, and decreased sleep quality (Peng & Dong, 2021). With a shortage of studies focusing on TikTok specifically, and due to it’s increase in popularity, we chose to narrow our study on the use of TikTok as it correlates to short-term memory. We determined that a widely accepted method to measure working memory capacity is the Automated Operation Span task, also referred to as OSPAN.

Study Design:

Research Question: Does using TikTok negatively affect working memory?

Hypothesis 1: Participants will be less accurate in their letter recall in an OSPAN test after recent TikTok usage compared to exposure to calming music.

Hypothesis 2: Participants will take more time to recall the letters in an OSPAN test after recent TikTok usage compared to exposure to calming music.

Within-Subject experiment: all participants were exposed to both filler tasks

Independent variable: filler task of listening to music or of using TikTok

Dependent variables: We measured OSPAN score, the time to recall letters, and self-reported frequency of TikTok usage

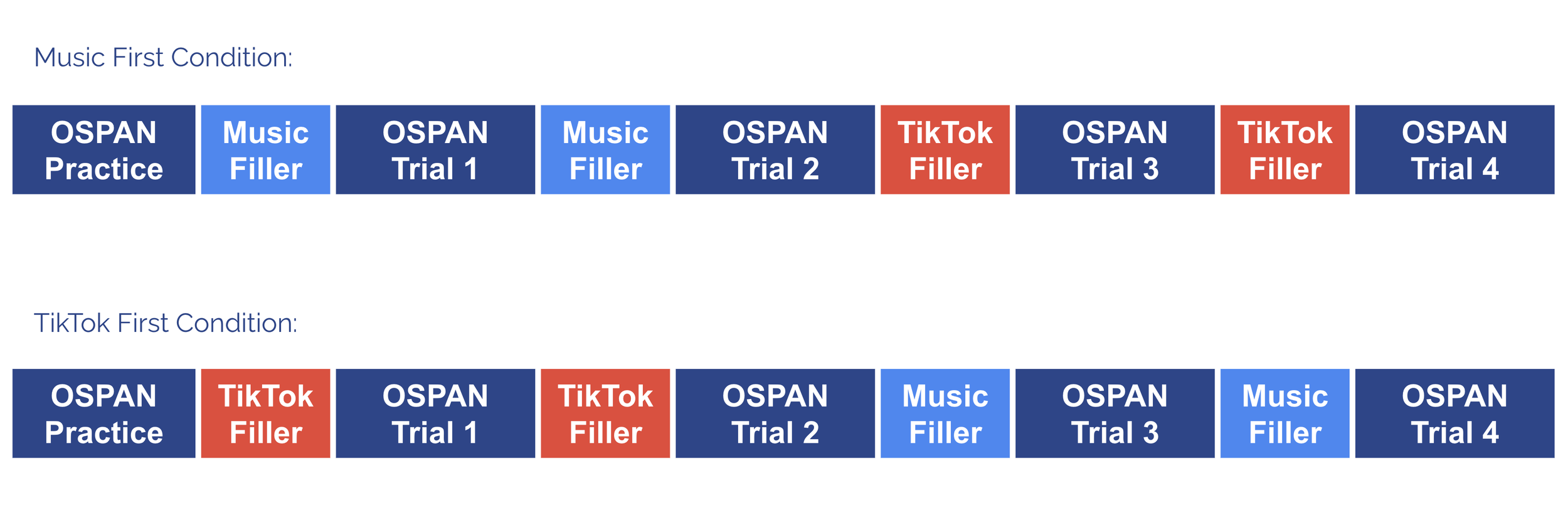

Participants: We accumulated 16 participants from a convenience sample of family, friends, and colleagues. To account for learning effect and task fatigue, half our participants completed the Music First Condition and half completed the TikTok First Condition.

Results:

Hypothesis 1: Our participant’s OSPAN scores were higher, and thus had better letter recall in trials after using TikTok than after listening to music. A paired-samples t test confirmed that this difference was significant. This refuted our first hypothesis in which we thought OSPAN scores would be significantly lower after the TikTok filler task.

Hypothesis 2: Our participant’s answered faster in trials following TikTok than in trials after listening to music. While this difference was not significant, it was the opposite of our second hypothesis in which we thought participants’ task times would be higher (slower) after the TikTok filler task.

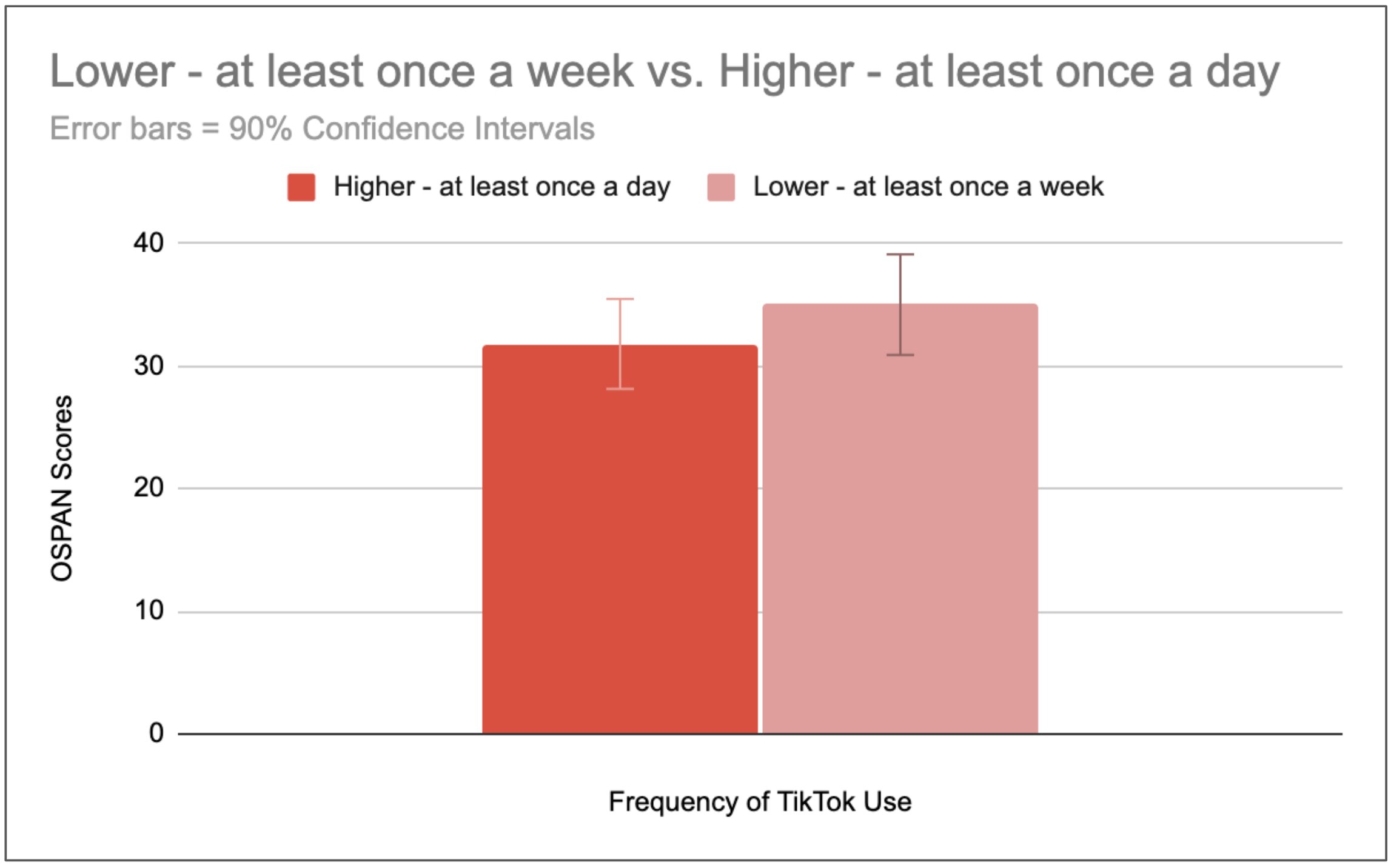

Extra Analysis: In a post-study questionnaire we inquired about how many hours participants would estimate they use TikTok. 10 of our participants claimed they used TikTok at least once a day. The other 6 reported using TikTok less frequently, about once a week or less.

We separated these two groups of participants and then compared their overall OSPAN scores for all tasks. We found that mean overall mean OSPAN scores were higher for those who reported using TikTok less frequently than those who reported using TikTok with greater frequency. (Higher OSPAN score means better letter recall which is associated with better working memory). An independent-samples t test confirmed this difference was not significant.

Conclusion:

The results of our study do not support either of our hypotheses. Although one of our results was statistically significant, we still did not have sufficient data to claim TikTok’s positive or negative effect on working memory.

Looking further at our study, we speculated the following:

Since most of our studies were conducted in the middle of the work day, it’s possible that deep thinking occurred during music filler tasks, and thus listening to music was more cognitively taxing than we planned. It’s possible that using TikTok allowed participants to turn their brain off, which allowed for greater functioning during the next OSPAN trial.

Since most of our participants were TikTok users, they were used to this kind of stimuli.

Our sample was narrow and homogenous. Most were women in their thirties living in the United States.

Refections:

Because one of our results was statistically significant, it would be interesting to explore this further with a larger sample size.

A distinction in the research question — were we curious about whether TikTok has an effect on working memory immediately after use? Or were we curious about whether regular, sustained TikTok use has an effect on working memory in general?

In order to analyze the ladder, we would want to conduct a between subjects experiment and find participants who are similar cognitively except for their TikTok usage.

I enjoyed the binary clarity of collecting and analyzing data that either supported or refuted our initial hypotheses; however, there was more gray area to account for in terms of study design and participant selection to be able to make claims about the greater population.